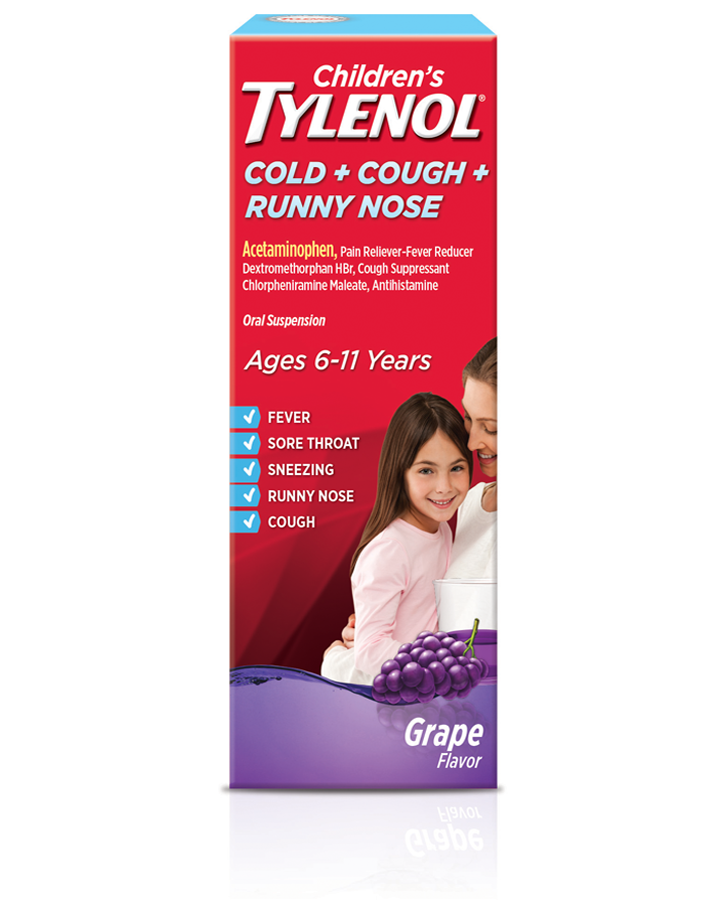

An acute acetaminophen overdose depletes hepatic glutathione stores by 70% to 80% hence, not all NAPQI can be metabolized. Glutathione, present in the hepatic tissue, binds to NAPQI and produces a nontoxic byproduct that subsequently is excreted by the kidneys. This biotransformation creates a reactive, highly toxic metabolite called N-acetyl- p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). Four percent of the remaining acetaminophen dose is biotransformed by the hepatic cytochrome P-450 system. The primary metabolic pathways occurring in hepatic tissue are sulfation, which predominates in children younger than 12 years old, and glucuronidation, which prevails in adolescents and adults. The kidneys excrete the water-soluble byproducts of this hepatic metabolism, and a small amount (about 2%) is urinated as unchanged acetaminophen. The presence of a coingestant that delays gastric emptying, or an overdose with an extended-release formulation of acetaminophen, further increases this time.Īfter ingestion, 90% to 95% of acetaminophen metabolism takes place in the liver ( Figure 1). When an acute overdose occurs, the peak serum concentration increases to 4 hours for immediate-release preparations. Peak serum concentrations are achieved at about 2 hours postingestion. Standard therapeutic oral doses of acetaminophen are rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, primarily in the small intestine. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity due to chronic overdose (also known as repeated supratherapeutic acetaminophen ingestion) is not discussed. This review article discusses the pathophysiology of acetaminophen metabolism, the clinical and diagnostic clues of an acute overdose, differential diagnoses, and management approaches for pediatric patients. 3 A single acute overdose can be life threatening due to the risk of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity, potentially leading to liver failure and death. 2ĭespite its excellent safety profile when properly dispensed, acetaminophen is cited as one of the drugs that is most often ingested in childhood poisonings. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved an intravenous preparation of acetaminophen (trade name Ofirmev) for inpatient use in children older than 2 years of age. Brand names of some acetaminophen-based medications are Tylenol, Panadol, Māpap, FeverAll, and Tempra. Many formulations with different concentrations of acetaminophen are available, including liquid suspensions, tablets, capsules, and rectal suppositories with a paraffin base. Today, acetaminophen (chemical name N-acetyl- p-aminophenol, or APAP known as paracetamol in most countries outside of the United States and Canada) is readily accessible and is an ingredient in more than 200 over-the-counter and prescription medications, either as a single agent or in combination with other pharmaceuticals. 1 The increased use of acetaminophen since the 1960s stems from the association of aspirin-containing medications with the occurrence of Reye syndrome in children. consumers purchased more than 28 billion doses of products containing acetaminophen. Key words: acetaminophen, paracetamol, N-acetyl- p-aminophenol (APAP), acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity, N-acetyl- p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), glutathione, sulfation, liver transaminases, centrilobular hepatic necrosis, Rumack-Matthew nomogram, N-acetylcysteine (NAC)Īcetaminophen is the most commonly used analgesic–antipyretic medication given to children in the United States and worldwide.

This article reviews the pathophysiology of acetaminophen metabolism, the clinical and diagnostic clues of an acute overdose, differential diagnoses, and management approaches including the use of the antidote, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), for acute acetaminophen overdose and toxicity in pediatric patients.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/old-acetaminophen-56a6fc193df78cf7729147ca.jpg)

ABSTRACT: Acetaminophen is the most commonly used pain medication in the United States, and its ubiquity results in its being one of the most frequently implicated drugs in childhood poisonings.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)